Appendix: How LLLPG fits into LeMP & Enhanced C#

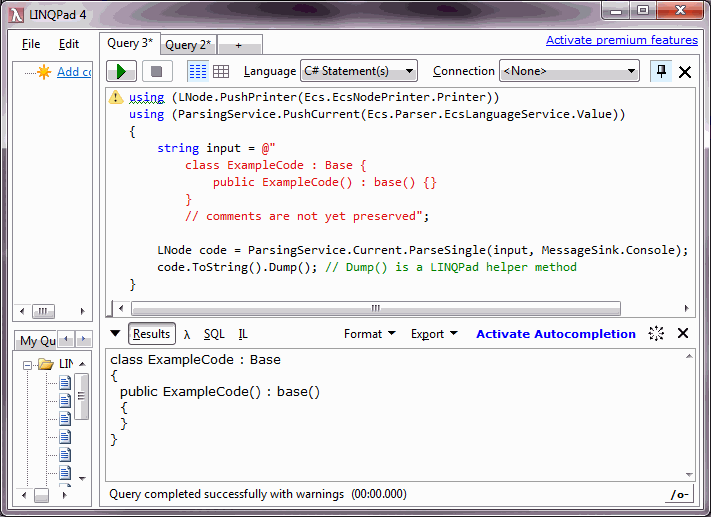

Updated Mar 2019So here’s the deal. I designed a language called Enhanced C#. It’s supposed to be about 99.9% backward compatible with C#, and the parser is about 95% complete (Let me know if you’re waiting for C# 7 support.) There is no EC# compiler yet, but there is a parser and a printer; so you use the parser + LeMP + printer and feed the output to the plain C# compiler. With a few lines of code, you can parse a block of EC# code and print it out again:

using (LNode.PushPrinter(Ecs.EcsNodePrinter.Printer))

using (ParsingService.PushCurrent(Ecs.Parser.EcsLanguageService.Value))

{

string input = @"{ your_code_here(Any_EC#_code_will_work); }";

LNode code = ParsingService.Current.ParseSingle(input, MessageSink.Console);

string output = code.ToString();

}

Since EC# is a superset of C#, LLLPG is able to produce C# code by using the EC# printer, as long as it only uses the C# subset of the language.

Originally, LLLPG grammars had to be written in LES code. LES is not a programming language, it is just a syntax and nothing else. One of the core ideas of the Loyc project is to “modularize” programming languages into a series of re-usable components. So instead of writing one big compiler for a language, a compiler is built by mixing and matching components. One of those components is the Loyc tree (the LNode class in Loyc.Syntax.dll). Another component is the LES parser (which is a text representation for Loyc trees). A third component is the EC# parser, a fourth component is the EC# printer, and a fifth component is LeMP, the macro processor.

Macros

Macros are a fundamental feature of LISP that I am porting over to the wider world of non-LISP languages.

A macro (in the LISP sense, not in the C/C++ sense) is simply a method that takes a syntax tree as input, and produces another syntax tree as output. Here’s an example of a macro written in plain C#:

[LexicalMacro("A := B", "Equivalent to 'var A = B'.", ":=")]

public static LNode ColonEquals(LNode node, IMessageSink sink)

{

var a = node.Args;

if (a.Count == 2) {

LNode A = a[0], B = a[1];

return F.Vars(F.Missing, F.Assign(A, B));

}

return null;

}

This macro takes a “colon equals” assignment written in LES or EC# like x := 123 and transforms it into a “variable declaration” like var x = 123; in C#.

The input, x := 123, is represented as a call to := with two arguments, x (an identifier, or Id for short) and 123 (a literal). ColonEquals() is designed to transform the call to :=. It checks that there are two arguments, extracts them from the input tree, and uses an LNodeFactory F (a static field whose declaration is not shown here) to produce the output tree.

Currently, the output syntax tree could be expressed in LES as #var(@``, x = 123). The C# node printer considers #var(type, name = value) to represent an (assigned) variable declaration, and prints it with the more familiar syntax “type name = value”.

By the way, macros are a bit easier to write in Enhanced C#. The above macro could be expressed in EC# as follows:

[LexicalMacro("A := B", "Equivalent to 'var A = B'.", ":=")]

public static LNode ColonEquals(LNode node, IMessageSink sink)

{

matchCode (node) {

case $A := $B:

return quote { var $A = $B; };

default:

return null;

}

}

If you think that’s cool, you might want to read my article about C# code generation and analysis.

Relationship with LLLPG

The point is, LLLPG is defined as a “macro” that takes your LLLPG (lexer) { ... }; or LLLPG (parser) { ... }; statement as input, and returns another syntax tree that represents C# source code. As a macro, it can live in harmony with other macros like the ColonEquals macro.

LLLPG: The Origin Story

In order to allow LLLPG to support EC#, I needed a EC# parser. But how would I create a parser for EC#? Obviously, I wanted to use LLLPG to write the parser, but without any parser there was no easy way to submit a grammar to LLLPG! After writing the LLLPG core engine and the EC# printer, here’s what I did to create the EC# parser:

- I used C# operator overloading and helper methods as a rudimentary way to write LLLPG parsers in plain C# (example test suite).

- Writing parsers this way is very clumsy, so I decided that I couldn’t write the entire EC# parser this way. Instead, I designed a new language that is syntactically much simpler than EC#, called LES. This language would serve not only as the original input language for LLLPG, but as a general syntax tree interchange format—a way to represent syntax trees of any programming language: “xml for code”.

- I wrote a lexer and parser for LES by calling LLLPG programmatically in plain C# (with operator overloading etc.)

- I wrote the

MacroProcessor(which I later named “LeMP”, short for “Lexical Macro Processor”) and a wrapper class calledCompilerthat provides the command-line interface.MacroProcessor’s job is to scan through a syntax tree looking for calls to “macros”, which are source code transformers (more on that below). It calls those transformers recursively until there are no macro calls left in the code. Finally,Compilerprints the result as text. - I built a small “macro language” on top of LES which combines LeMP (the macro processor) with a set of small macros that makes LES look a lot like C#. The macros are designed to convert LES to C# (you can write C# syntax trees directly in LES, but they are a bit ugly.)

- I wrote some additional macros that allow you to invoke LLLPG from within LES.

- I hacked the LES parser to also be able to parse LLLPG code like

@{ a* | b }in a derived class (a shameful abuse of “reusable code”). - I wrote a lexer and parser for LES in LES itself.

- I published the first article about LLLPG in Oct 2013.

- I wrote the lexer and parser of EC# in LES, in the process uncovering a bunch of new bugs in LLLPG (which I fixed)

- I added one extra macro to support LLLPG in EC#.

- Finally, to test the EC# parser, I rewrote the grammar of LLLPG in EC#.

- I excitedly unveiled it in Feb 2014… with little fanfare.

So now you can write LLLPG parsers in EC#! Yay!

LLLPG’s input languages: EC# & LES

Enhanced C# (EC#)

As I mentioned, Enhanced C# is a language based on C# whose compiler isn’t done yet (I’m looking for volunteers to help.) The parser is practically done, though, so I can talk about some of the new syntax that EC# supports. Actually there is quite a bit of new syntax in EC#; let me just tell you about the syntax that is relevant to LLLPG.

Token literals

Loyc.Syntax.Lexing.TokenTree eightTokens = @{

This token tree has eight children

(specifically, six identifiers and two parentheses.

The tokens inside the parentheses are children of the opening '('.)

};

LLLPG is a “domain-specific language” or DSL, which means it’s a special-purpose language (for creating parsers).

Token trees are a technique for allowing DSLs (Domain-Specific Languages) without any need for “dynamic syntax” in the host language. Unlike some “extensible” languages, EC# and LES do not have “extensible” parsers: you cannot add new syntax to them. However, EC# and LES do have token literals, which are collections of tokens. After a source file has been parsed, a macro can run its own parser on a token tree that is embedded in the larger syntax tree. That’s what LLLPG does.

EC# allows token trees in any location where an expression is allowed. It also allows you to use a token tree instead of a method body, or instead of a property body. So when the EC# parser encounters statements like these:

rule Bar @{ "Bar" };

rule int Foo(int x) @{ 'F' 'o' 'o' {return x;} };

The parser actually sees these as property or method declarations. LLLPG’s ECSharpRule macro then transforms them into a different form, shown here:

#rule(void, Foo, (), "Bar");

#rule(int, Foo, (#var(int, x),), ('F', 'o', 'o', { return x; }));

(A separate macro recognizes the LES-specific syntax for rules and produces this common form.)

The main LLLPG macro is in charge of turning this into the final output:

void Bar()

{

Match('B');

Match('a');

Match('r');

}

int Foo(int x)

{

Match('F');

Match('o');

Match('o');

return x;

}

Note: you may also see token literals with square brackets @[...]. This means the same thing as @{...}; there are two syntaxes for a historical reason.

Block-call statements

get { return _foo; }

set { _foo = value; }

In C#, you may have noticed that “get” and “set” are not keywords. Not unless they are inside a property declaration, that is. In C#, they “become” keywords based on their location.

EC# generalizes this concept. In EC#, get and set are never keywords no matter where they appear. Instead, get {...} and set {...} are merely examples of a new kind of statement, the block-call statement, which has two forms:

identifier { statements; } identifier (argument, list) { statements; }

These statements are considered exactly equivalent to method calls of the following form:

identifier({ statements; }); identifier(argument, list, { statements; });

So the LLLPG block:

LLLPG (parser(laType(TokenType), matchType(int))) {

rule Foo @{ ... };

}

Is a block-call statement, equivalent to

LLLPG (parser(laType(TokenType), matchType(int)), {

rule Foo @{...};

});

Blocks as expressions

string fraction = "0.155";

float percent = 100 * { if (!float.TryParse(fraction, out float tmp)) tmp = -1; tmp };

In EC#, {braced blocks} can be used as expressions, which explains what a method call like foo(x, { y(z) }) means. When a block is used inside an expression, like this, the final statement in the block becomes the return value of the block as a whole, when there is no semicolon on the end of the final statement. In this case, tmp is the result of the block, so percent will be set to 15.5. Or rather, it will be set to 15.5 after the EC# compiler is written. Until then, this is merely an interesting but useless syntax tree.

In the case of a statement like

LLLPG (parser(laType(TokenType), matchType(int)), { rule Foo @{...}; });

Everything in parenthesis is passed to a macro belonging to LLLPG, which (to make a long story short) transforms it into C# code.

That’s enough information to understand how LLLPG works. Hopefully now you understand the concept of LLLPG as a DSL embedded in EC#.

Loyc Expression Syntax (LES)

When LLLPG was first released, you had to write parsers in LES since the EC# parser hadn’t been written, so a large section of this article was devoted to LES - a language that is very comparable to Enhanced C#, but dramatically easier to parse.

If you’d like to see how you can write “C# code” in LES, I’ve separated that information into a separate page.

All LES-based parsers now need to have the following first line:

import macros LeMP.Prelude.Les;

Originally this was not required because the LES “prelude” macros were imported automatically. However, the LES prelude could potentially interfere with normal C# code, so it is no longer imported automatically (the macro compiler doesn’t know anything about the input language, so it is unaware of whether it should import the macros or not).