This page has moved to ecsharp.net.

GitHub doesn't support HTTP redirects, so you'll be redirected via JavaScript in 5 seconds.LLLPG Part 3: Beyond the basics

23 Feb 2014 (updated 22 May 2016)This page is obsolete

The LLLPG manual has been reorganized. These old articles may be deleted in the future.

Welcome to part 3

New to LLLPG? Start at part 1.

There are lots of things left to cover, so let’s get started. LLLPG 1.1.0 was released at the same time as this article; much has changed since then, so this article was mostly rewritten in May 2016. For more detailed info about LLLPG’s newest features, see Part 5.

A brief overview of the Loyc libraries

When writing a parser, you have to decide whether you’ll use the Loyc runtime libraries or not; the main advantage of not using them is that you won’t have to distribute the 3 Loyc DLLs with your application. But they contain a lot of useful stuff, so have a look and see if you like them.

The important library for parsers based on LLLPG is Loyc.Syntax.dll, which depends on Loyc.Essentials.dll and Loyc.Collections.dll. These DLLs have documentation for most of the classes they contain, automatically available to VS IntelliSense through Loyc.Syntax.xml, Loyc.Essentials.xml and Loyc.Collections.xml.

In brief, let me just say very briefly what these libraries are for and what they contain.

Loyc.Essentials.dll is a library of general-purpose code that supplements the .NET BCL (standard libraries). It contains the following categories of stuff:

- Collection stuff: interfaces, adapters, helper classes, base classes, extension methods, and implementations for simple “core” collections such as InternalList. You can learn more in the docs, but note that the documentation also shows the collections from Loyc.Collections.dll since it’s all in the same namespace,

Loyc.Collections. - Geometry: simple generic geometric interfaces and classes, e.g.

Point<T>andVector<T> - Math: generic math interfaces that allow arithmetic to be performed in generic code. Also includes fixed-point types, 128-bit integer math, and handy extra math functions in

MathEx. - Other utilities: message sinks (

IMessageSink),Symbol, threading stuff, a miniture clone of NUnit (MiniTest,RunTests), and miscellaneous [“global” functions] and extension methods.Compatibility: a very small amount of .NET 4.5 stuff, backported to .NET 4.0 when using the .NET 4 build.

Loyc.Essentials also defines ICharSource (defined in Loyc.Essentials.dll), a standard interface for a source of characters, which is used by lexers. string converts implicitly to UString which is a string slice structure that implements ICharSource. The Slice(start, count) extension method can also get slices of strings.

IMessageSink serves as a simple, generic logging interface. It is recommended that your parsers report warnings and errors to an IMessageSink object. You can use MessageSink.Console to print (colored) errors to the console, MessageSink.Null to suppress output, and MessageSink.FromDelegate((type, context, message, args) => {...}) to customize error handling.

The ParseHelpers class has generic number parsers that are handy for lexers, such as TryParseDouble, which can parse numbers of any reasonable radix and is therefore useful for hex float literals such as 0xF.Fp+1 (a syntax that represents 31.875).

Loyc.Collections.dll is a library of data structures, mostly rather complex ones, currently all written by me:

- VLists: this data structure is notable because Loyc nodes (

LNodes) useVList<LNode>for their arguments and attributes. This is an implementation detail that ideally you wouldn’t have to know about; but C# has notypedefs that I could use to hide the type, and since VLists arestructs, if you treat them asIList<T>they will be boxed, and you don’t really want that. - ALists, including the B+tree-like data structures

BList<T>,BDictionary<K,V>, and my favorite,BMultiMap<K,V>, plus the newSparseAList<T>which I use in my syntax highlighter. Bijection<K1,K2>: A dictionary that goes in both directions.- And more!

Loyc.Syntax.dll provides the foundations for LLLPG and contains the reference implementation of LES, the syntax tree interchange format:

BaseLexeris the recommended base class for lexers created with LLLPG.BaseParserForList<Token,MatchType>is the recommended base class for parsers.StreamCharSourceis an implementation ofICharSourcedesigned for parsing a file without storing the whole thing in memory.ISourceFileencapsulates anICharSource, a file name string, and a mapping to translate character indexes to (line, column) pairs and back. It is derived fromIIndexPositionMapper.SourceRangeis a triple (ISourceFile Source,int StartIndex,int Length) that represents a range of characters in a source file.SourcePosis a (filename, line, column) triple. WhileSourceRangeis a struct so it can be stored compactly,SourcePosis assumed to be used much less often, and it is a class so it can be derived fromLineAndColwhich is a (line, column) pair.IndexPositionMapperprovides mapping fromSourceRangetoSourcePosand back, but you don’t necessarily need this class becauseBaseLexeralready keeps track of the current line number (and where it started). In your lexer, you must callAfterNewline()at each newline in order for index-position mapping to work correctly.LNodeis a Loyc Tree. Parsers commonly useLNodeFactoryto help constructLNodes.LesLanguageService.Valueprovides an LES parser and printer. It implementsIParsingService.SourceFileWithLineRemapsis a helper class for languages that have a#linedirective.Precedence: a simple but flexible standard representation for the concept of operator precedence and “miscibility”.CodeSymbolsis astatic classfilled with standardSymbols used in Loyc trees for operators (Addfor +,Subfor -,Mulfor *,Assignfor =,Eqfor==, …), statements (Classfor#class,Enumfor #enum,ForEachfor #foreach, …), modifiers (Privatefor #private,Staticfor #static,Virtualfor #virtual, …), types (Voidfor#void,Int32for#int32, Double for#double, …), and so on.

The Loyc libraries contain only “safe”, verifiable code.

Configuring LLLPG

LLLPG can be invoked either with the custom tool for Visual Studio, or on the command line (or in a pre-build step) by running LLLPG.exe filename.

The following command-line options are reported by LLLPG –help, but command-line options are rarely necessary.

--forcelang: Specifies that --inlang overrides the input file extension.

Without this option, known file extensions override --inlang.

--help: show this screen

--inlang=name: Set input language: --inlang=ecs for Enhanced C#, --inlang=les for LES

--macros=filename.dll: load macros from given assembly

--max-expand=N: stop expanding macros after N nested or iterated expansions.

--noparallel: Process all files in sequence

--nostdmacros: Don't scan LeMP.StdMacros.dll or pre-import LeMP and LeMP.Prelude

--outext=name: Set output extension and optional suffix:

.ecs (Enhanced C#), .cs (C#), .les (LES)

This can include a suffix before the extension, e.g. --outext=.output.cs

If --outlang is not used, output language is chosen by file extension.

--outlang=name: Set output language independently of file extension

--parallel: Process all files in parallel (this is the default)

--set:key=literal: Associate a value with a key (use #get(key) to read it back)

--snippet:key=code: Associate code with a key (use #get(key) to read it back)

--timeout=N: Aborts the processing thread(s) after this many seconds (0=never)

--verbose: Print extra status messages (e.g. discovered Types, list output files).

Some of these options, such as --verbose and --timeout=N, are supported in the LLLPG Custom Tool; you can put command-line options in the “Custom Tool Namespace” field in Visual Studio.

Note: in VS, the [Verbosity(N)] grammar attribute doesn’t work without the --verbose option.

In your *.ecs or *.les input file, the syntax for invoking LLLPG is to use one of these statements:

LLLPG(lexer) { /* rules */ };

LLLPG(lexer(...options...)) { /* rules */ };

LLLPG(parser) { /* rules */ };

LLLPG(parser(...options...)) { /* rules */ };

LLLPG { /* parser mode is the default */ };

(LES requires the semicolon while EC# does not, and LES files permit LLLPG lexer {...} and LLLPG parser {...} without parenthesis, which (due to the syntax rules of LES) is exactly equivalent to LLLPG(lexer) {...} or LLLPG(parser) {...}).

The following options are available for both lexer and parser:

inputSource: vandinputClass: T: used bystaticlexers/parsers and parsers instructs. See part 5 for more information.terminalType: T: data type of terminals. This is used by the colon operator, e.g.x:Terminal, which becomesx = Match(Terminal)in the output, declares a variablexof this type to store the terminal.setType: T: data type for large sets. When you write a set with more than four elements, such as'a'|'e'|'i'|'o'|'u'|'y', LLLPG generates a set object and usesset.Contains(la0)for prediction andMatch(set)for matching, e.g. instead ofMatch('a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u', 'y')it generates a set with a statement likestatic HashSet<int> RuleName_set0 = NewSet('a', 'e', 'i', 'o', 'u', 'y');and then callsMatch(RuleName_set0). The default isHashSet<int>.listInitializer: e: Sets the data type of lists declared automatically when you use the+:operator. An initializer likeType x = exprcausesTypeto be used as the list type andexpras the initialization expression. TheTypecan have a type parameterTthat is replaced with the appropriate item type. The default islistInitializer: List<T> = new List<T>().

The following options are available only for parser:

laType: T: data type ofla0,la1, etc. Typically this is the name of anenumthat you are using to represent token types (default:int). For lexers,laTypeis alwaysint(notchar, because -1 is used for EOF).matchCast: T: causes a cast to be added to all token types passed toMatch. For example, if you usematchCast: intoption, it will change calls likeMatch('+', '-')intoMatch((int) '+', (int) '-').matchCastis a synonym formatchType.allowSwitch: bool: whether to allowswitchstatements (default:true). In C#, switch cases must be constants, so certainlaTypedata types likeSymbolare incompatible withswitch. Therefore, this option can be used to preventswitchstatements from being generated. Requires a boolean literaltrueorfalse(@trueor@falsein LES).castLa: bool: whether to cast the result ofLA0andLA(i)tolaType(the default istrue)

The above options apply to the lexer or parser helper object, which controls code generation and defines how terminals are interpreted:

lexermode requires numeric terminals, and allows numeric ranges like1..31or'a'..'z'parsermode permits any literal or complex identifier, but does not support numeric ranges.

In addition to the lexer and parser options, you can add one or more of the following attributes before the LLLPG statement:

[FullLLk(true)]: enables deeper prediction analysis (as explained later)[Verbosity(int)]: prints extra messages to help debug a grammar. An integer literal is required and specifies how much detail to print:1for basic information,2for extra information,3for excessive information. Details printed include first sets, follow sets, and prediction trees. Note: This attribute does not work without the--verboseoption.[NoDefaultArm(true)]: adds a call toError(...)at all branching points for which you did not provide adefaultorerrorarm (see §”Error handling mechanisms” below).[LL(int)](synonyms:[k(int)]and[DefaultK(int)]): specifies the default maximum number of lookahead characters or tokens in this grammar.[AddComments(false)]: by default, a comment line is printed in the output file in front of the code generated for every Alts (branching point:| / * ?).[AddComments(false)]removes these comments.

Boilerplate

“Boilerplate” is repetitive code you must write every time you do a task. Because LLLPG leaves you in charge of defining token types and controlling the overall parsing process, a bit more boilerplate is required in LLLPG than in most parser generators; but the benefit is that there is less magic going on: you can see how everything works, and hopefully learn to control it if you need to.

When parsing a typical programming language, you need two stages (Lexing and Parsing) although some languages, such as JSON, are simple enough to parse in a single stage (lexer and parser combined into a single LLLPG “lexer”), and some languages (such as PHP or Liquid) might benefit from more than two stages. The Enhanced C# parser has four stages: lexer, preprocessor (for #if, #region, etc.), tree parser, and main parser).

The official two-stage boilerplate example is included in the LLLPG-Samples repository, but let’s review a snapshot of it (May 2016). Now, no IntelliSense (code completion) is available in .ecs files, so it can be useful to split your Lexer and Parser classes between two files, and that’s what the boilerplate example does. In the Grammars.cs file, IntelliSense will be available and in the Grammars.ecs file you put your grammar code.

Typically you start by defining a token types:

public enum TokenType

{

EOF = 0, // End-of-file. Conventional to use 0 so that default(Token) is EOF

Newline = 1,

Number = 2,

/* TODO: add more token names here */

}

The lexing stage produces tokens that are sent to the parser, but how you store tokens is up to you. You could define your own Token structure, like this:

public struct Token : ISimpleToken<TokenType>

{

public Token(int type, int startIndex, int length, object value = null)

{

Type = type; StartIndex = startIndex; Length = length; Value = value;

}

/// <summary>The category of the token (integer, keyword, etc.) used as

/// the primary value for identifying the token in a parser.</summary>

TokenType Type { get; set; }

/// <summary>Character index where the token starts in the source file.</summary>

int StartIndex { get; set; }

int Length { get; set; }

/// <summary>Value of the token. The meaning of this property is defined

/// by the particular implementation of this interface, but typically this

/// property contains a parsed form of the token (e.g. if the token came

/// from the text "3.14", its value might be <c>(double)3.14</c>.</summary>

object Value { get; }

}

But you can also use the default Token in the Loyc.Syntax.Lexing namespace in Loyc.Syntax.dll; the boilerplate makes the latter choice. In that case we should define this extension method on it because the default Token just uses a raw int as the token type:

public static class TokenExt {

public static TokenType Type(this Token t)

{ return (TokenType)t.TypeInt; }

}

Boilerplate Lexer

Because LLLPG doesn’t control the overall lexing and parsing processes (unlike in, for example, ANTLR), you need a little more boilerplate code to indicate how lexing will work. Here’s the lexer boilerplate in the Grammars.cs file:

partial class Lexer : BaseILexer<ICharSource, Token>

{

// When using the Loyc libraries, `BaseLexer` and `BaseILexer` read character

// data from an `ICharSource`, which the string wrapper `UString` implements.

public Lexer(string text, string fileName = "")

: this((UString)text, fileName) { }

public Lexer(ICharSource text, string fileName = "")

: base(text, fileName) { }

private int _startIndex;

// Creates a Token

private Token T(TokenType type, object value)

{

return new Token((int)type, _startIndex, InputPosition - _startIndex, value);

}

// Gets the text of the current token that has been parsed so far

private UString Text()

{

return CharSource.Slice(_startIndex, InputPosition - _startIndex);

}

}

This class is derived from BaseILexer rather than BaseLexer so that it implements ILexer<Token>, which includes IEnumerator<Token>. This is useful because it will let us use the Buffered() extension method later, which lazily converts IEnumerator<T> into IList<T>.

And here is the rest of the boilerplate in the Grammars.ecs file, plus a Newline and Number rule to get you started:

partial class Lexer

{

LLLPG (lexer); // Lexer starts here

public override rule Maybe<Token> NextToken() @{

(' '|'\t')* // ignore spaces

{_startIndex = InputPosition;}

// this is equivalent to (t:Newline / t:Number / ...) { return t; }:

( any token in t:token { return t; } // `any token` requires v1.8.0

/ EOF { return Maybe<Token>.NoValue; }

)

}

private new token Token Newline @{

('\r' '\n'? | '\n') {

AfterNewline(); // increment the current LineNumber

return T(TT.Newline, WhitespaceTag.Value);

}

};

private token Token Number() @{

'0'..'9'+ ('.' '0'..'9'+)? {

var text = Text();

return T(TT.Number, ParseHelpers.TryParseDouble(ref text, radix: 10));

}

};

// TODO: define more tokens here

}

You might want to change this to strip out newlines so that the parser never sees them:

public override rule Maybe<Token> NextToken() @{

(' '|'\t'|Newline)* // ignore spaces and newlines

{_startIndex = InputPosition;}

( any token in t:token { return t; } // `any token` requires v1.8.0

/ EOF { return Maybe<Token>.NoValue; }

)

}

// Since our newline rule no longer returns a token, we can use `extern`

// to inherit the implementation of the Newline method in the base class

// (but we still need to specify its grammar so LLLPG knows when to call it.)

// Notice that this is marked "rule" and not "token" so it is ignored by

// the "any token in ..." command above.

extern rule Newline @{ '\n' | '\r' '\n'? };

Boilerplate Parser

LLLPG 1.4+ requires less boilerplate code than previous versions, but we still need to define

- A top-level

Parsemethod that combines your parser with your lexer - A constructor

- A method that converts a token type integer to a string (for error reporting)

You’ll find that code in Grammars.cs:

partial class Parser : BaseParserForList<Token, int>

{

public static List<double> Parse(string text, string fileName = "")

{

var lexer = new Lexer(text, fileName);

// Lexer is derived from BaseILexer, which implements IEnumerator<Token>.

// Buffered() is an extension method that gathers the output of the

// enumerator into a list so that the parser can consume it.

var parser = new Parser(lexer.Buffered(), lexer.SourceFile);

return parser.Numbers();

}

protected Parser(IList<Token> list, ISourceFile file, int startIndex = 0)

: base(list, default(Token) /* EOF token */, file, startIndex) {}

// Used for error reporting

protected override string ToString(int tokenType) {

return ((TokenType)tokenType).ToString();

}

}

BaseParserForList<Token, int> is a new base class in LLLPG 1.4+ that assumes your tokens are stored in an IList<Token>; int is the data type of token types (unfortunately it is not legal to use your enum TokenType here because for some reason TokenType does not implement IEquatable<TokenType> which means that it is impossible for BaseParserForList to compare two TokenTypes efficiently. That’s why int is used instead.

Finally, you need some kind of grammar. The boilerplate code in Grammars.ecs simply puts numbers into a list:

partial class Parser { LLLPG (parser(matchType: int, laType: TokenType, terminalType: Token));

rule List<double> Numbers @{

// $result is special to LLLPG. It's the return value of the rule.

{$result = new List<double>();}

(n:TT.Number {$result.Add((double)n.Value);})*

}; }

The laType option tells LLLPG that your actual token type is TokenType. The matchType: int option is required because the base class uses int instead. And the terminalType: Token indicates that when you write something like n:TT.Number, the data type of n should be Token.

Producing a Loyc syntax tree

Normally, you’ll use {actions} in the grammar to produce syntax tree objects. You can either design your own syntax tree, or use immutable Loyc trees (LNodes). Let’s try out LNode.

LNode has static methods for constructing nodes, but it’s more convenient to use LNodeFactory which keeps track of the current source file (ISourceFile) and provides a wider variety of methods for constructing nodes. So let’s start by modifying the constructor to create an LNodeFactory:

LNodeFactory F;

protected Parser(IList<Token> list, ISourceFile file, int startIndex = 0)

: base(list, default(Token), file, startIndex) { F = new LNodeFactory(file); }

Now, let’s make a really small “language” that supports addition, subtraction, and “function calls”. So let’s create add some new token types for that:

public enum TokenType

{

EOF = 0, // End-of-file. If we choose 0, default(Token) is EOF

Number = 2, // Number, e.g. 3.3

Id = 3, // Identifier, e.g. foo bar x y

LParen = 4, // (

RParen = 5, // )

Comma = 6, // ,

Add = 10, // +

Sub = 11, // -

}

Next, let’s expand the lexer to recognize the new tokens Id, LParen, etc.:

private token Token Id() @{

('a'..'z'|'A'..'Z'|'_')

('a'..'z'|'A'..'Z'|'_'|'0'..'9')* {

return T(TT.Id, (Symbol) Text().ToString());

}

};

private token Token LParen() @{ '(' { return T(TT.LParen, null); } };

private token Token RParen() @{ ')' { return T(TT.RParen, null); } };

private token Token Comma() @{ ',' { return T(TT.Comma, null); } };

private token Token Operator()

@{ '+' { return T(TT.Add, CodeSymbols.Add); }

| '-' { return T(TT.Sub, CodeSymbols.Sub); }

};

Recall that T() is a helper method, defined above, for creating a Token. You could define a separate rule for each operator, but the code is a bit shorter if you combine all operators into a single token rule.

Note that when creating the operator tokens, we set the value to one of the predefined symbols in CodeSymbols, because LNode uses Symbol to represent all identifiers and operator names, so we will use the Symbol later when constructing the syntax tree. To specify a Symbol that does not exist in CodeSymbols, you can cast any string to Symbol (e.g. (Symbol)"string"). The benefit of Symbol over string is that comparing Symbols is as fast as comparing two integers; this is because == is not overloaded: equality is defined as reference equality, as there is only one instance of a given Symbol.

Finally, we need to write a grammar for our new language. In Grammars.ecs, replace the Parser class with this code:

partial class Parser

{

LLLPG (parser(matchType: int, laType: TokenType, terminalType: Token,

listInitializer: VList<T> _ = new VList<T>()));

alias("(" = TT.LParen);

alias(")" = TT.RParen);

alias("+" = TT.Add);

alias("-" = TT.Sub);

alias("," = TT.Comma);

rule LNode ExpressionAndEof @{

// Usually you should define a rule that checks for EOF at the end,

// otherwise bad input like "5 x" can parse successfully (as a literal 5)

result:Expression EOF

};

rule LNode Expression @{

result:PrimaryExpr

[ // Infix operator

op:("+"|"-") PrimaryExpr {$result = F.Call((Symbol) op.Value, $result, $PrimaryExpr);}

]*

};

rule LNode PrimaryExpr @{

result:Atom

[ // Method call

"(" ExpressionList ")" {$result = F.Call($result, $ExpressionList);}

]*

};

rule VList<LNode> ExpressionList @{

result+:Expression ["," result+:Expression]*

};

rule LNode Atom

@{ t:TT.Number { return F.Literal(t); }

| t:TT.Id { return F.Id(t); }

| "(" Expression ")" { return F.InParens($Expression); }

| error {Error(0, "Expected subexpression");}

(_|EOF) { return F.Missing; }

};

}

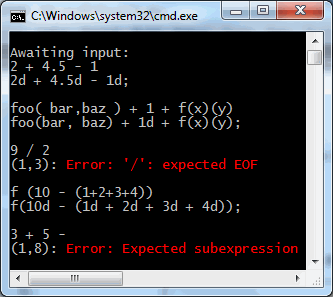

I took the liberty of adding a bit of manual error handling in the last rule, as discussed later.

Finally, you’ll need to change the Parser.Parse function (in Grammars.cs) to call Expression instead of Numbers:

public static LNode Parse(string text, string fileName = "")

{

var lexer = new Lexer(text, fileName);

var parser = new Parser(lexer.Buffered(), lexer.SourceFile);

return parser.ExpressionAndEof();

}

Finally, go to Main() and change the way the input line is printed:

Console.WriteLine(Parser.Parse(line));

This will print the LNode with the default printer, which produces LES code.

You’re done! You should now have a working parser that creates Loyc trees.

Rules with parameters and return values

You can add parameters and a return value to any rule, and use parameters when calling any rule:

// Define a rule that takes an argument and returns a value.

// Matches a pattern like TT.Num TT.Comma TT.Num TT.Comma TT.Num...

// with a length that depends on the 'times' argument.

token double Mul(int times) @[

x:=TT.Num

nongreedy(

&{times>0} {times--;}

TT.Comma y:=Num

{x *= y;})*

{return x;}

];

// To call a rule with a parameter, add a parameter list after

// the rule name.

rule double Mul3 @[ x:=Mul(3) {return x;} ];

Here’s the code generated for this parser:

double Mul(int times)

{

int la0, la1;

var x = Match(TT.Num);

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == TT.Comma) {

if (times > 0) {

la1 = LA(1);

if (la1 == Num) {

times--;

Skip();

var y = MatchAny();

x *= y;

} else

break;

} else

break;

} else

break;

}

return x;

}

double Mul3()

{

var x = Mul(3);

return x;

}

There is a difference between Foo(123) and Foo (123) with a space. Foo(123) calls the Foo rule with a parameter of 123; Foo (123) is equivalent to Foo 123 so the rule (or terminal) Foo is matched followed by the number 123 (which is “{” in ASCII).

Parameters to recognizers

As you learned in the last article, each rule can have a recognizer form which is called by syntactic predicates &(...). The recognizer always has a return type of bool, regardless of the return type of the main rule, and any action blocks {...} are removed from the recognizer (currently there is no way to keep an action block, sorry.)

You can cause parameters to be kept or discarded from a recognizer using a recognizer attribute on a rule. Observe how code is generated for the following rule:

LLLPG(parser) {

[recognizer { void FooRecognizer(int x); }]

token double Foo(int x, int y) @[ match something ];

token double FooCaller(int x, int y) @[

Foo(1) Foo(1, 2) &Foo(1) &Foo(1, 2)

];

}

The recognizer version of Foo will accept only one argument because the recognizer attribute specifies only one argument. Although the recognizer attribute uses void as the return type of FooRecognizer, LLLPG ignores this and changes the return type to bool:

double Foo(int x, int y)

{

Match(match);

Match(something);

}

bool Try_FooRecognizer(int lookaheadAmt, int x)

{

using (new SavePosition(this, lookaheadAmt))

return FooRecognizer(x);

}

bool FooRecognizer(int x)

{

if (!TryMatch(match))

return false;

if (!TryMatch(something))

return false;

return true;

}

double FooCaller(int x, int y)

{

Foo(1);

Foo(1, 2);

Check(Try_FooRecognizer(0, 1), "Foo");

Check(Try_FooRecognizer(0, 1, 2), "Foo");

}

Notice that LLLPG does not verify that FooCaller passes the correct number of arguments to Foo or FooRecognizer, not in this case anyway. So LLLPG does not complain or alter the incorrect call Foo(1) or Try_FooRecognizer(0, 1, 2). Usually LLLPG will simply repeat the argument argument list you provide, whether it makes sense or not. However, as a normal rule is “converted” into a recognizer, LLLPG can automatically reduce the number of arguments to other rules called by that rule, as demonstrated here:

[recognizer {void BarRecognizer(int x);}]

token double Bar(int x, int y) @[ match something ];

rule void BarCaller @[

Bar(1, 2)

];

rule double Start(int x, int y) @[ &BarCaller BarCaller ];

Generated code:

double Bar(int x, int y)

{

Match(match);

Match(something);

}

bool Try_BarRecognizer(int lookaheadAmt, int x)

{

using (new SavePosition(this, lookaheadAmt))

return BarRecognizer(x);

}

bool BarRecognizer(int x)

{

if (!TryMatch(match))

return false;

if (!TryMatch(something))

return false;

return true;

}

void BarCaller()

{

Bar(1, 2);

}

bool Try_Scan_BarCaller(int lookaheadAmt)

{

using (new SavePosition(this, lookaheadAmt))

return Scan_BarCaller();

}

bool Scan_BarCaller()

{

if (!BarRecognizer(1))

return false;

return true;

}

double Start(int x, int y)

{

Check(Try_Scan_BarCaller(0), "BarCaller");

BarCaller();

}

Notice that BarCaller() calls Bar(1, 2), with two arguments. However, Scan_BarCaller, which is the auto-generated name of the recognizer for BarCaller, calls BarRecognizer(1) with only a single parameter. Sometimes a parameter that is needed by the main rule (Bar) is not needed by the recognizer form of the rule (BarRecognizer) so LLLPG lets you remove parameters in the recognizer attribute; LLLPG will automatically delete call-site parameters when generating the recognizer version of a rule. You must only remove parameters from the end of the argument list; for example, if you write

[recognizer { void XRecognizer(string second); }]

rule double X(int first, string second) @[ match something ];

LLLPG will not notice that you removed the first parameter rather than the second, it will only notice that the recognizer has a shorter parameter list, so it will only remove the second parameter. Also, LLLPG will only remove parameters from calls to the recognizer, not calls to the main rule, so the recognizer cannot accept more arguments than the main rule.

Saving inputs

LLLPG recognizes five operators for “assigning” a token or return value to a variable: :, =, :=, += and +:.

:=usesvarto creates a variable in-place to hold a token or return value.:creates a variable at the top of the method to hold a token or return value. Because the variable is created separately, LLLPG must “guess” the correct data type for the variable. This may require you to specify theterminalTypeoperation, and there are situations where you can’t use this operator (e.g. LLLPG doesn’t understand inheritance, so if you assign the same variable multiple times from different sources, LLLPG expects the type to be identical each time.)=Assigns a value to a variable that you have declared manually.+=Assumes the left-hand side is a list that you have declared manually; callsAddon that list.+:Adds a token or return value to a list, but asks LLLPG to create the list.

This table how code is generated for these operators:

| Operator | Example | Generated code for terminal | Generated code for nonterminal |

|---|---|---|---|

= |

x=Foo |

x = Match(Foo); |

x = Foo(); |

:= |

x:=Foo |

var x = Match(Foo); |

var x = Foo(); |

: |

x:Foo |

// Use with `terminalType: Token`

|

// RetType refers to Foo's return type

|

+= |

lst+=Foo |

lst.Add(Match(Foo)); |

lst.Add(Foo()); |

+: |

lst+:Foo |

// Use with `terminalType: Token`

|

// RetType refers to Foo's return type

|

You can match one of a set of terminals, for example x:=('+'|'-'|'.') generates code like var x = Match('+', '-', '.') (or var x = Match(set) for some set object, for large sets). However, currently LLLPG does not support matching a list of nonterminals, e.g. x:=(A()|B()) is not supported.

In LLLPG 1.3.2 I added a feature where you would write simply Foo instead of foo:=Foo and then write $Foo in code later, which retrospectively saves the value returned from Foo in an “anonymous” variable. For example, instead of writing code like this:

private rule LNode IfStmt() @{

{LNode els = null;}

t:=TT.If "(" cond:=Expr ")" then:=Stmt

greedy[TT.Else els=Stmt]?

{return IfNode(t, cond, then, els);}

};

It would be written like this instead:

private rule LNode IfStmt() @{

TT.If "(" Expr ")" Stmt

greedy[TT.Else els:Stmt]?

{return IfNode($(TT.If), $Expr, $Stmt, els);}

};

This makes the grammar look less cluttered. Note that if the optional branch is skipped, the variable els ends up with its default value (null); the same would happen with $Expr, if Expr were optional.

Error handling mechanisms in LLLPG

Admittedly, I’m not 100% sure what the right way to do error handling is, but LLLPG does give you enough flexibility, I think.

First of all, when matching a single terminal, LLLPG puts your own code in charge of error handling. For example, if the rule says

rule PlusMinus @{ '+'|'-' };

the generated code is

void PlusMinus()

{

Match('-', '+');

}

So LLLPG is relying on the Match() method to decide how to handle errors. If the next input is neither '-' nor '+', what should Match() do:

- Throw an exception?

- Print an error, consume one character and continue?

- Print an error, keep

InputPositionunchanged and continue?

I’m not sure what the best approach is, but by default, BaseLexer throws a LogException. You can modify the ErrorSink property to avoid throwing; for example, use MessageSink.Console to write errors to the terminal.

Currently, all the Match methods of BaseLexer/BaseILexer and BaseParser/BaseParserForList do not consume the current character or token when an error occurs.

For cases that require if/else chains or switch statements, LLLPG’s default behavior is optimistic: Quite simply, it assumes there are no erroroneous inputs. When you write

rule Either @{ 'A' | B };

the output is

void Either()

{

int la0;

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == 'A')

Skip();

else

B();

}

Under the assumption that there are no errors, if the input is not 'A' then it must be B. Therefore, when you are writing a list of alternatives and one of them makes sense as a catch-all or default, you should put it last in the list of alternatives, which will make it the default. You can also specify which branch is the default by writing the word default at the beginning of one alternative:

rule B @{ 'B' };

rule Either @{ default 'A' | B };

// Output

void B()

{

Match('B');

}

void Either()

{

int la0;

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == 'A')

Match('A');

else if (la0 == 'B')

B();

else

Match('A');

}

Remember that, if there is ambiguity between alternatives, the order of alternatives controls their priority. So you have at least two reasons to change the order of different alternatives:

- To give one priority over another when the alteratives overlap

- To select one as the default in case of invalid input

Occasionally these goals are in conflict: you may want a certain arm to have higher priority and also be the default. That’s where the default keyword comes in. In this example, the “Consonant” arm is the default:

LLLPG(lexer)

{

rule ConsonantOrNot @{

('A'|'E'|'I'|'O'|'U') {Vowel();} / 'A'..'Z' {Consonant();}

};

}

void ConsonantOrNot()

{

switch (LA0) {

// (Newlines between cases removed for brevity)

case 'A': case 'E': case 'I': case 'O': case 'U':

{

Skip();

Vowel();

}

break;

default:

{

MatchRange('A', 'Z');

Consonant();

}

break;

}

}

You can use the default keyword to mark the “vowel” arm as the default instead, in which case perhaps we should call it “non-consonant” rather than “vowel”:

LLLPG(lexer) {

rule ConsonantOrNot @{

default ('A'|'E'|'I'|'O'|'U') {Other();}

/ 'A'..'Z' {Consonant();}

};

}

The generated code will be somewhat different:

static readonly HashSet<int> ConsonantOrNot_set0 = NewSet('A', 'E', 'I', 'O', 'U');

void ConsonantOrNot()

{

do {

switch (LA0) {

case 'A': case 'E': case 'I': case 'O': case 'U':

goto match1;

case 'B': case 'C': case 'D': case 'F': case 'G':

case 'H': case 'J': case 'K': case 'L': case 'M':

case 'N': case 'P': case 'Q': case 'R': case 'S':

case 'T': case 'V': case 'W': case 'X': case 'Y':

case 'Z':

{

Skip();

Consonant();

}

break;

default:

goto match1;

}

break;

match1:

{

Match(ConsonantOrNot_set0);

Other();

}

} while (false);

}

This code ensures that the first branch matches any character that is not in one of the ranges ‘B’..’D’, ‘F’..’H’, ‘J’..’N’, ‘P’..’T’, or ‘V’..’Z’, i.e. the non-consonants (Note: this behavior was added in LLLPG 1.0.1; LLLPG 1.0.0 treated default as merely reordering the alternatives.)

Specifying a default branch should never change the behavior of the generated parser when the input is valid. The default branch is invoked when the input is unexpected, which means it is specifically an error-handling mechanism.

Note: (A | B | default C) is usually, but not always, the same as (A | B | C). Roughly speaking, in the latter case, LLLPG will sometimes let A or B handle invalid input if the code will be simpler that way.

Another error-handling feature is that LLLPG can insert error handlers automatically, in all cases more complicated than a call to Match. This is accomplished with the [NoDefaultArm(true)] grammar option, which causes an Error(int, string) method to be called whenever the input is not in the expected set. Here is an example:

//[NoDefaultArm]

LLLPG(parser)

{

rule B @{ 'B' };

rule Either @{ ('A' | B)* };

}

// Output

void B()

{

Match('B');

}

void Either()

{

int la0;

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == 'A')

Skip();

else if (la0 == 'B')

B();

else

break;

}

}

When [NoDefaultArm] is added, the output changes to

void Either()

{

int la0;

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == 'A')

Skip();

else if (la0 == 'B')

B();

else if (la0 == EOF)

break;

else

Error(0, "In rule 'Either', expected one of: (EOF|'A'|'B')");

}

}

The error message is predefined, and [NoDefaultArm] is not currently supported on individual rules.

This mode probably isn’t good enough for professional grammars so I’m taking suggestions for improvements. The other way to use this feature is to selectively enable it in individual loops using default_error. For example, this grammar produces the same output as the last one:

LLLPG(parser)

{

rule B @{ 'B' };

rule Either @{ ['A' | B | default_error]* };

}

default_error must be used by itself; it does not support, for example, attaching custom actions.

Finally, you can customize the error handling for a particular loop using an error branch:

LLLPG

{

rule B @[ 'B' ];

rule Either @{

[ 'A'

| B

| error {Error(0, ""Anticipita 'A' aŭ B ĉi tie"");} _

]*

};

}

In this example I’ve written a custom error message in Esperanto; here’s the output:

void B()

{

Match('B');

}

void Either()

{

int la0;

for (;;) {

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == 'A')

Skip();

else if (la0 == 'B')

B();

else if (la0 == EOF)

break;

else {

MatchExcept();

Error("Anticipita 'A' aŭ B ĉi tie");

}

}

}

Notice that I used _ inside the error branch to skip the invalid terminal. The error branch behaves very similarly to a default branch except that it does not participate in prediction decisions. A formal way to explain this would be to say that (A | B | ... | error E) is equivalent to (A | B | ... | default ((~_) => E)), although I didn’t actually implement it that way, so maybe it’s not perfectly equivalent.

One more thing that I think I should mention about error handling is the Check() function, which is used to check that an &and predicate matches. Previously you’ve seen an and-predicate that makes a prediction decision, as in:

token Number @[

{dot::bool=false;}

('.' {dot=true;})?

'0'..'9'+ (&{!dot} '.' '0'..'9'+)?

];

In this case '.' '0'..'9'+ will only be matched if !dot:

...

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == '.') {

if (!dot) {

la1 = LA(1);

if (la1 >= '0' && la1 <= '9') {

Skip();

Skip();

for (;;) {

...

The code only turns out this way because the follow set of Number is _*, as explained in the next article where I talk about the difference between token and rule. Due to the follow set, LLLPG assumes Number might be followed by '.' so !dot must be included in the prediction decision. But if Number is a normal rule (and the follow set of Number does not include '.'):

rule Number @[

{dot::bool=false;}

('.' {dot=true;})?

'0'..'9'+ (&{!dot} '.' '0'..'9'+)?

];

Then the generated code is different:

...

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == '.') {

Check(!dot, "!dot");

Skip();

MatchRange('0', '9');

for (;;) {

...

In this case, when LLLPG sees '.' it decides to enter the optional item (&{!dot} '.' '0'..'9'+)? without checking &{!dot} first, because '.' is not considered a valid input for skipping the optional item. Basically LLLPG thinks “if there’s a dot here, matching the optional item is the only reasonable thing to do”. So, it assumes there is a Check(bool, string) method, which it calls to check &{!dot} after prediction.

Currently you can’t (in general) force an and-predicate to be checked as part of prediction; prediction analysis checks and-predicates only when needed to resolve ambiguity. Nor can you suppress Check statements or override the second parameter to Check. Let me know if this limitation is causing problems for you.

That’s it for error handling in LLLPG!

A random fact

Did you know? Unlike ANTLR, LLLPG does not care much about parenthesis when interpreting loops and alternatives separated by | or /. For example, all of the following rules are interpreted the same way and produce the same code:

rule Foo1 @{ ["AB" | "A" | "CD" | "C"]* };

rule Foo2 @{ [("AB" | "A" | "CD" | "C")]* };

rule Foo3 @{ [("AB" | "A") | ("CD" | "C")]* };

rule Foo4 @{ ["AB" | ("A" | "CD") | "C"]* };

rule Foo5 @{ ["AB" | ("A" | ("CD" | "C"))]* };

The loop (*) and all the arms are integrated into a single prediction tree, regardless of how you might fiddle with parenthesis. Knowing this may help you understand error messages and generated code better.

Another thing that is Good to Know™ is that | behaves differently when the left and right side are terminals. ('1'|'3'|'5'|'9' '9') is treated not as four alternatives, but only two: ('1'|'3'|'5') | '9' '9', as you can see from the generated code:

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == '1' || la0 == '3' || la0 == '5')

Skip();

else {

Match('9');

Match('9');

}

This happens because a “terminal set” is always a single unit in LLLPG, i.e. multiple terminals like ('A'|'B') are combined and treated the same as a single terminal 'X', whenever the left and right sides of | are both terminal sets. If you insert an empty code block into the first alternative, it is no longer treated as a simple terminal, LLLPG cannot join the terminals into a single set anymore. In that case LLLPG sees four alternatives instead, causing different output:

rule Foo@[ '1' {/*empty*/} | '3' | '5' | '9' '9' ];

void Foo()

{

int la0;

la0 = LA0;

if (la0 == '1')

Skip();

else if (la0 == '3')

Skip();

else if (la0 == '5')

Skip();

else {

Match('9');

Match('9');

}

}

End of part 3

The following topics still remain for future articles:

FullLLkversus “approximate” LL(k)tokenversusrule.- Managing ambiguity.

- The API that LLLPG uses. You’ve seen it already, of course, I just need to write a complete reference.

- Advanced techniques: tree parsing, keyword parsing, collapsing many precedence levels into a single rule, and other tricks used by the EC# parser.

- All about Loyc and its libraries. Things you can do with LeMP: other source code manipulators besides LLLPG.

Are you using LLLPG to parse an interesting language? Please leave a comment!

Comments