6. How to write parser

30 May 2016In this article, I’ll explain all the “boilerplate” code you’ll need in an LLLPG-based two-stage parser, and then I’ll show you how to produce a syntax tree using the LNode class in Loyc.Syntax.dll.

Boilerplate

“Boilerplate” is repetitive code you must write every time you do a task. Because LLLPG leaves you in charge of defining token types and controlling the overall parsing process, a bit more boilerplate is required in LLLPG than in most parser generators; but the benefit is that there is less magic going on: you can see how everything works, and hopefully learn to control it if you need to.

When parsing a typical programming language, you need two stages (Lexing and Parsing) although some languages, such as JSON, are simple enough to parse in a single stage (lexer and parser combined into a single LLLPG “lexer”), and some languages (such as PHP or Liquid) might benefit from more than two stages. The Enhanced C# parser has four stages: lexer, preprocessor (for #if, #region, etc.), tree parser, and main parser).

The official two-stage boilerplate example is included in the LLLPG-Samples repository, but let’s review a snapshot of it (May 2016). Now, no IntelliSense (code completion) is available in .ecs files, so it can be useful to split your Lexer and Parser classes between two files, and that’s what the boilerplate example does. In the Grammars.cs file, IntelliSense will be available and in the Grammars.ecs file you put your grammar code.

Typically you start by defining a token types:

public enum TokenType

{

EOF = 0, // End-of-file. Conventional to use 0 so that default(Token) is EOF

Newline = 1,

Number = 2,

/* TODO: add more token names here */

}

The lexing stage produces tokens that are sent to the parser, but how you store tokens is up to you. You could define your own Token structure, like this:

public struct Token : ISimpleToken<TokenType>

{

public Token(int type, int startIndex, int length, object value = null)

{

Type = type; StartIndex = startIndex; Length = length; Value = value;

}

/// <summary>The category of the token (integer, keyword, etc.) used as

/// the primary value for identifying the token in a parser.</summary>

TokenType Type { get; set; }

/// <summary>Character index where the token starts in the source file.</summary>

int StartIndex { get; set; }

int Length { get; set; }

/// <summary>Value of the token. The meaning of this property is defined

/// by the particular implementation of this interface, but typically this

/// property contains a parsed form of the token (e.g. if the token came

/// from the text "3.14", its value might be <c>(double)3.14</c>.</summary>

object Value { get; }

}

But you can also use the default Token in the Loyc.Syntax.Lexing namespace in Loyc.Syntax.dll; the boilerplate makes the latter choice. In that case we should define this extension method on it because the default Token just uses a raw int as the token type:

public static class TokenExt {

public static TokenType Type(this Token t)

{ return (TokenType)t.TypeInt; }

}

Boilerplate Lexer

Because LLLPG doesn’t control the overall lexing and parsing processes (unlike in, for example, ANTLR), you need a little more boilerplate code to indicate how lexing will work. Here’s the lexer boilerplate in the Grammars.cs file:

partial class Lexer : BaseILexer<ICharSource, Token>

{

// When using the Loyc libraries, `BaseLexer` and `BaseILexer` read character

// data from an `ICharSource`, which the string wrapper `UString` implements.

public Lexer(string text, string fileName = "")

: this((UString)text, fileName) { }

public Lexer(ICharSource text, string fileName = "")

: base(text, fileName) { }

private int _startIndex;

// Creates a Token

private Token T(TokenType type, object value)

{

return new Token((int)type, _startIndex, InputPosition - _startIndex, value);

}

// Gets the text of the current token that has been parsed so far

private UString Text()

{

return CharSource.Slice(_startIndex, InputPosition - _startIndex);

}

}

This class is derived from BaseILexer rather than BaseLexer so that it implements ILexer<Token>, which includes IEnumerator<Token>. This is useful because it will let us use the Buffered() extension method later, which lazily converts IEnumerator<T> into IList<T>.

And here is the rest of the boilerplate in the Grammars.ecs file, plus a Newline and Number rule to get you started:

partial class Lexer

{

LLLPG (lexer); // Lexer starts here

public override rule Maybe<Token> NextToken() @{

(' '|'\t')* // ignore spaces

{_startIndex = InputPosition;}

// this is equivalent to (t:Newline / t:Number / ...) { return t; }:

( any token in t:token { return t; } // `any token` requires v1.8.0

/ EOF { return Maybe<Token>.NoValue; }

)

}

private new token Token Newline @{

('\r' '\n'? | '\n') {

AfterNewline(); // increment the current LineNumber

return T(TT.Newline, WhitespaceTag.Value);

}

};

private token Token Number() @{

'0'..'9'+ ('.' '0'..'9'+)? {

var text = Text();

return T(TT.Number, ParseHelpers.TryParseDouble(ref text, radix: 10));

}

};

// TODO: define more tokens here

}

You might want to change this to strip out newlines so that the parser never sees them:

public override rule Maybe<Token> NextToken() @{

(' '|'\t'|Newline)* // ignore spaces and newlines

{_startIndex = InputPosition;}

( any token in t:token { return t; } // `any token` requires v1.8.0

/ EOF { return Maybe<Token>.NoValue; }

)

}

// Since our newline rule no longer returns a token, we can use `extern`

// to inherit the implementation of the Newline method in the base class

// (but we still need to specify its grammar so LLLPG knows when to call it.)

// Notice that this is marked "rule" and not "token" so it is ignored by

// the "any token in ..." command above.

extern rule Newline @{ '\n' | '\r' '\n'? };

Boilerplate Parser

LLLPG 1.4+ requires less boilerplate code than previous versions, but we still need to define

- A top-level

Parsemethod that combines your parser with your lexer - A constructor

- A method that converts a token type integer to a string (for error reporting)

You’ll find that code in Grammars.cs:

partial class Parser : BaseParserForList<Token, int>

{

public static List<double> Parse(string text, string fileName = "")

{

var lexer = new Lexer(text, fileName);

// Lexer is derived from BaseILexer, which implements IEnumerator<Token>.

// Buffered() is an extension method that gathers the output of the

// enumerator into a list so that the parser can consume it.

var parser = new Parser(lexer.Buffered(), lexer.SourceFile);

return parser.Numbers();

}

protected Parser(IList<Token> list, ISourceFile file, int startIndex = 0)

: base(list, default(Token) /* EOF token */, file, startIndex) {}

// Used for error reporting

protected override string ToString(int tokenType) {

return ((TokenType)tokenType).ToString();

}

}

BaseParserForList<Token, int> is a new base class in LLLPG 1.4+ that assumes your tokens are stored in an IList<Token>; int is the data type of token types (unfortunately it is not legal to use your enum TokenType here because for some reason TokenType does not implement IEquatable<TokenType> which means that it is impossible for BaseParserForList to compare two TokenTypes efficiently. That’s why int is used instead.

Finally, you need some kind of grammar. The boilerplate code in Grammars.ecs simply puts numbers into a list:

partial class Parser

{

LLLPG (parser(laType: TokenType, matchType: int, terminalType: Token));

rule List<double> Numbers @{

// $result is special to LLLPG. It's the return value of the rule.

{$result = new List<double>();}

(n:TT.Number {$result.Add((double)n.Value);})*

};

}

The laType option tells LLLPG that your token type enum is TokenType. The matchType: int option is required because the base class uses int instead. And the terminalType: Token indicates that when you write something like n:TokenType.Number, the data type of n should be Token.

Producing a Loyc syntax tree

Normally, you’ll use {actions} in the grammar to produce syntax tree objects. You can either design your own syntax tree, or use immutable Loyc trees (LNodes). Let’s try out LNode.

LNode has static methods for constructing nodes, but it’s more convenient to use LNodeFactory which keeps track of the current source file (ISourceFile) and provides a wider variety of methods for constructing nodes. So let’s start by modifying the constructor to create an LNodeFactory:

LNodeFactory F;

protected Parser(IList<Token> list, ISourceFile file, int startIndex = 0)

: base(list, default(Token), file, startIndex) { F = new LNodeFactory(file); }

Now, let’s make a really small “language” that supports addition, subtraction, and “function calls”. So let’s create add some new token types for that:

public enum TokenType

{

EOF = 0, // End-of-file. If we choose 0, default(Token) is EOF

Number = 2, // Number, e.g. 3.3

Id = 3, // Identifier, e.g. foo bar x y

LParen = 4, // (

RParen = 5, // )

Comma = 6, // ,

Add = 10, // +

Sub = 11, // -

}

Next, let’s expand the lexer to recognize the new tokens Id, LParen, etc.:

private token Token Id() @{

('a'..'z'|'A'..'Z'|'_')

('a'..'z'|'A'..'Z'|'_'|'0'..'9')* {

return T(TT.Id, (Symbol) Text().ToString());

}

};

private token Token LParen() @{ '(' { return T(TT.LParen, null); } };

private token Token RParen() @{ ')' { return T(TT.RParen, null); } };

private token Token Comma() @{ ',' { return T(TT.Comma, null); } };

private token Token Operator()

@{ '+' { return T(TT.Add, CodeSymbols.Add); }

| '-' { return T(TT.Sub, CodeSymbols.Sub); }

};

Recall that T() is a helper method, defined above, for creating a Token. You could define a separate rule for each operator, but the code is a bit shorter if you combine all operators into a single token rule.

Note that when creating the operator tokens, we set the value to one of the predefined symbols in CodeSymbols, because LNode uses Symbol to represent all identifiers and operator names, so we will use the Symbol later when constructing the syntax tree. To specify a Symbol that does not exist in CodeSymbols, you can cast any string to Symbol (e.g. (Symbol)"string"). The benefit of Symbol over string is that comparing Symbols is as fast as comparing two integers; this is because == is not overloaded: equality is defined as reference equality, as there is only one instance of a given Symbol.

Finally, we need to write a grammar for our new language. In Grammars.ecs, replace the Parser class with this code:

partial class Parser

{

LLLPG (parser(matchType: int, laType: TokenType, terminalType: Token,

listInitializer: VList<T> _ = new VList<T>()));

alias("(" = TT.LParen);

alias(")" = TT.RParen);

alias("+" = TT.Add);

alias("-" = TT.Sub);

alias("," = TT.Comma);

rule LNode ExpressionAndEof @{

// Usually you should define a rule that checks for EOF at the end,

// otherwise bad input like "5 x" can parse successfully (as a literal 5)

result:Expression EOF

};

rule LNode Expression @{

result:PrimaryExpr

[ // Infix operator

op:("+"|"-") PrimaryExpr {$result = F.Call((Symbol) op.Value, $result, $PrimaryExpr);}

]*

};

rule LNode PrimaryExpr @{

result:Atom

[ // Method call

"(" ExpressionList ")" {$result = F.Call($result, $ExpressionList);}

]*

};

rule VList<LNode> ExpressionList @{

result+:Expression ["," result+:Expression]*

};

rule LNode Atom

@{ t:TT.Number { return F.Literal(t); }

| t:TT.Id { return F.Id(t); }

| "(" Expression ")" { return F.InParens($Expression); }

| error {Error(0, "Expected subexpression");}

(_|EOF) { return F.Missing; }

};

}

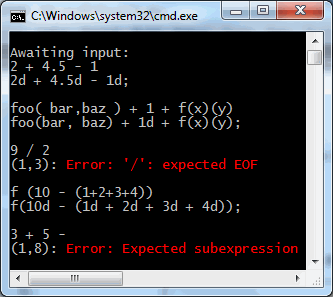

I took the liberty of adding a bit of manual error handling in the last rule, as discussed in Error Handling.

Finally, you’ll need to change the Parser.Parse function (in Grammars.cs) to call ExpressionAndEof instead of Numbers:

public static LNode Parse(string text, string fileName = "")

{

var lexer = new Lexer(text, fileName);

var parser = new Parser(lexer.Buffered(), lexer.SourceFile);

return parser.ExpressionAndEof();

}

Finally, go to Main() and change the way the input line is printed:

Console.WriteLine(Parser.Parse(line));

This will print the LNode with the default printer, which produces LES code.

You’re done! You should now have a working parser that creates Loyc trees.

For reference: things you must do when overriding BaseLexer and BaseParser

For lexing

The typical base class for lexing is BaseLexer, but you can specialize it as BaseLexer<UString>, which should (in theory) give higher perfomance if your input is always a string.

In either case, you must call AfterNewline() whenever you encounter a newline ('\n' | '\r' '\n'?) so that the LineNumber property is increased by one. BaseLexer also contains its own Newline rule, which you can incorporate into your lexer with

// 'extern' suppresses code generation, so the code is inherited

// from BaseLexer, and `'\r' '\n'? | '\n'` tells LLLPG what it does.

extern token Newline @{ '\r' '\n'? | '\n' };

BaseLexer additionally records the locations of all line breaks in its SourceFile property (which is protected) so you can call SourceFile.IndexToLine(i).Line to get the line number of any character that has been tokenized so far; this only works properly if you call AfterNewline consistently.

When LLLPG was first released, you had to override the abstract error handler:

protected abstract void Error(int lookaheadIndex, string message);

But now a default error handler is provided that throws LogException, and the normal way to change how errors are reported is not to override Error(), but instead to set the ErrorSink property, e.g. this causes errors to be printed to the terminal:

base.ErrorSink = Loyc.MessageSink.Console;

For parsing

When LLLPG was first released, you were expected to use BaseParser as your base class, which was tedious because you had to override all these methods:

protected abstract Int32 EofInt();

protected abstract Int32 LA0Int { get; }

protected abstract Token LT(int i);

protected abstract void Error(int li, string message);

protected abstract string ToString(Int32 tokenType);

Only one of the above APIs are required by LLLPG itself; the others help BaseParser implement the other APIs. In addition to the above, you had to implement the following APIs that are required by LLLPG and not provided by BaseParser:

// (typical implementation shown)

const TokenType EOF = TokenType.EOF;

TokenType LA0 { get { return LT0.Type(); } }

TokenType LA(int offset) { return LT(offset).Type(); }

Because using BaseParser was cumbersome, BaseParserForList<Token,MatchType> was introduced (and its specialized form BaseParserForList<Token,MatchType,List>). BaseParserForList<Token,MatchType> manages the list of tokens itself - any list that implements IList<Token> is acceptable, and the derived class constructor must pass a list of tokens to the base class, along with a token that represents EOF, and an ISourceFile (which you can get from the SourceFile property of BaseLexer):

protected BaseParserForList(IList<Token> list, Token eofToken, ISourceFile file, int startIndex=0);

BaseParserForList only requires you to implement a single abstract method, to convert MatchType to a string. MatchType is usually int in practise, so your implementation might look like this (if TokenType is the name of your token type enum):

protected override string ToString(int tokenType)

{

return ((TokenType)tokenType).ToString();

}

All the base classes have an InputPosition property. BaseLexer caches the current character in LA0 when InputPosition changes, while BaseParser caches the current token in LT0 when InputPosition changes.

Next up

If you like, you may also want to check out the JSON parser.

Otherwise, you can move on to next article in the series which is about error handling.